The second issue of the Australian Journal of Orchidology, published in 1959/1960, contains an interesting article by D. Stewart, a resident of Cairns, who lived for several years in Sikkim, a small Himalayan country sandwiched between Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan and India.

Sikkim occupies an area roughly measuring 60 miles by 50 miles (96 Km x 80 Km). Its altitude varies from about 500 feet (150 m) where the Teesta River valley enters India to over 6000 m at the top of several of its snow-bound mountain peaks. Sikkim lies between 26° and 27°N, roughly as far north of the equator as Brisbane is to the south. Because of the incredible range in altitudes for such a small country, Sikkim provides a wide variety of different orchid habitats. There are surprisingly few native animals and birds but “plenty of snakes and an abundance of leeches in the wet season”.

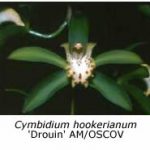

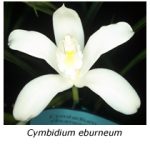

Stewart recorded that, at the southern entrance to the valley at an altitude of about 150 m, Vanda teres grew in the trees, together with Dendrobium moschatum with canes seven feet (2.1 m) long carrying multiple inflorescences. A little higher up the slopes Cymbidium eburneum, C. giganteum (now C. iridioides) and C. hookerianum grew in the forks of odd trees or on rocks in accumulated humus. In side valleys Thunia alba (regarded by some as synonymous with T. marshalliana) grew on the ground or on fallen trees, a particular fallen tree trunk some 30 feet (10 m) long being covered with flowering plants.

Further up the valley, at an altitude of 900 m, Dendrobium chrysanthum grew in the forks of trees, with D. densiflorum being found 300 m higher. On the more exposed ridges, at an altitude a little over 1200 m, Dendrobium nobile was found growing on the trunks and forks of trees, where it was exposed to a drier atmosphere and much more light than the other dendrobium species. D. hookerianum, a golden-flowered dendrobium with a lovely fimbriate lip, was found at intermediate levels in cool, shady gullies.

Coelogyne cristata grew on tree branches in cool gullies at an altitude of 1200 m, and C. elata (syn. C. stricta), C. corymbosa and C. ocellata were found at higher altitudes where temperatures were lower; C. ochracea (syn. C. nitida) and C. flaccida were found at lower levels. At an altitude of 1500 m clusters of Paphiopedilum venustum and P. insigne grew in humus-covered timber and ground beside the banks of streams. Various bulbophyllums and other unspecified orchids with small flowers grew at higher altitudes up to 2400 m. Although orchids were not found above 2400 m, the native rhododendrons began here, “huge trees forty and fifty feet high with large saucer- and bell-shaped flowers in yellow-gold, white-pink, red and purple, growing progressively smaller till at 15,000 ft (4500 m) acres of the lower slopes of the mountains were covered with a tangled mat, which in May was so densely covered with pale pink flowers that stem or leaf were invisible”.

Travel in Sikkim was quite arduous in Stewart’s day, there being no roads. Ponies were used at altitudes up to 2400 m but above that level horses “become useless because of the rarefied air. Yaks are then used to 15,000 ft. (4500 m). Mid-winter was clear and cool, frost being almost unknown below 1500 m. Torrential rain falls between early June and late September, followed by gradually cooling but still clear sunny days until mid-winter.

What an incredible variety of orchids there were in such a small area! Many, like Coelogyne cristata, Dendrobium nobile and the three cymbidium species, grow happily without heat in Melbourne but those found at lower altitudes need a little warmth in winter.