The average member of a Victorian orchid society would have a collection of a hundred or two plants, usually accommodated in one or two shade houses, and in some cases, also a heated glasshouse. We usually refer to ourselves as hobby growers or amateurs. Things were rather different a hundred years ago, when orchid growing was (at least in Britain) a hobby restricted to the seriously rich. These gentlemen growers (with the emphasis on gentlemen) wouldn’t think of involving themselves in such mundane matters as re-potting or watering -that was left to their ‘professional’ gardeners. Occasionally the orchid owners selected parents for pollination but their role for the most part was displaying their plants at prestigious shows, and buying more plants, often by auction and at obscene prices! Many of these gentlemen growers had large collections comprising many thousands of orchids, housed in extensive greenhouse complexes, that required the attention of teams of gardeners.

As an example, I can provide some details of the orchid collection of Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914), who made his fortune manufacturing screws in Birmingham before retiring from ‘trade’ to enter politics and, as a hobby, to grow orchids. He was very successful at both, becoming Lord Mayor of Birmingham before entering Parliament, where he held several important cabinet posts. Some idea of the size of Chamberlain’s orchid collection can be gained from the plan of his glasshouse complex in 1880, as shown in the introduction to Jim Rentoul’s book, The Specialist Orchid Grower (1987). Entered directly from Chamberlain’s house (Highbury) in Birmingham, it consisted of about twenty glasshouses connected by a glazed corridor. It included a boiler house, conservatory, fernery and pigeon roost. The entire complex measured roughly 70 m long by 12 m wide, the main rooms being lit by electric light, a novelty in those times! Individual houses were devoted to particular genera such as cattleyas, calanthes, phalaenopsis and East Indian orchids. One house held 2000-3000 odontoglossums, another over a thousand plants of Laelia anceps.

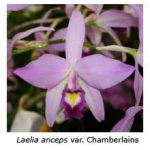

When in London, Chamberlain was never seen without an orchid flower in his buttonhole -two were sent to him from Birmingham every day! Two of his sons (Joseph Arthur and Arthur Neville) followed their father into Parliament, the younger (known as Neville) becoming Prime Minister in 1937. His negotiations with Hitler failed to avert war in 1939, and the rest is history! Joseph Chamberlain is commemorated by Laelia anceps var. Chamberlain’s and by Paphiopedilum chamberlainianum. Actually, he was not particularly fond of paphiopedilums and rather displeased when Frederick Sander named the species in his honour, especially when he saw its spiral petals. Chamberlain thought they resembled screws and that Sander was poking fun at him because of the way that his fortune had been gained (from a screw factory). In those days, gentlemen who had inherited their wealth through property looked down upon those who had prospered through trade, and Chamberlain was probably hoping that those in high society had forgotten how he had made his wealth! He can rest easy in his grave now, because the taxonomists have since changed the name Paphiopedilum chamberlainianum to Paphiopedilum victoria-regina. He was Vice-President of the Royal Orchid Society for many years and still held that position when he died in 1914.

Don’t get the impression that Joseph Chamberlain was the largest amateur orchid grower of his era, as there were many others with comparable collections, Sir George Holford, Sir Jeremiah Colman, Sir Trevor Lawrence and Baron Schroeder, just to name a few. Of course nurserymen such as Frederick Sander and Sons, Stuart Low & Co., and Charlesworth & Co. also featured in RHS reports of the times but always below the influential gentlemen growers, who considered themselves as amateurs, no matter how many gardeners they employed.